The Computational Poet

Alicia Guo on living poems, fertile nonsense, and writing beside the machine.

Alicia Guo is a computational poet and PhD student studying how creative writers actually use LLMs and other AI tools in the wild.

Language and words are her medium, and her practice makes behaviours like drafting, deleting, prompting, and iterating visible as art — poems that respond, mutate, and sometimes refuse to settle. We talk about fertile nonsense, authorship when the tool is alive, intentionally designing scarcity for digital work, and what governance might look like when models are trained on writers — or when writers use models. Along the way, we explore the craft of collaboration with machines that stay full of surprise.

I was going through your Nuggets and I noticed that yesterday you had put in a new one. You wrote,

Could you break this down for me?

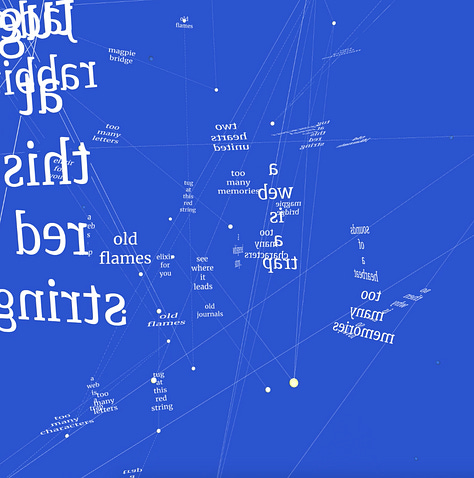

I actually don’t even remember posting this! [laughs] I am working on a piece about co-writing with AI – it’s for a more experimental magazine called Ensemble Park. They’re looking at new writing processes with AI, and the thing I created/dubbed was Cephalopoet – it looks like this multi-armed tentacle thing where, when I edit one piece of text, two more will spring up.

So it’s proliferating like a Hydra where, when you make edits, it spirals out of control. That text was actually the system prompt that I used. I just really love these sorts of random nonsense generations, where you are then tasked with making meaning.

What do you mean by ‘changing the direction of words’?

Let’s say you input a poem – you have a central node that then branches out. You can read it non-linearly, you can collapse it, but every time you want to make an edit, it keeps expanding.

So much of the conversation, when we talk about working with AI, is about control. You want to control the output. It’s about the control that you give to creatives, the control you give to people. And this is an experiment of what if we didn’t have that, if constantly regenerating wasn’t an option or if it had a cost?

I’m the kind of person who gets stuck in the possibility space; it’s tough for me to narrow down sometimes. So what if I just don’t give myself that option? It started off as very frustrating, but became a joyful experience of creating and letting go.

You call yourself a computational poet. What is a computational poet and what kinds of artifacts are you working on?

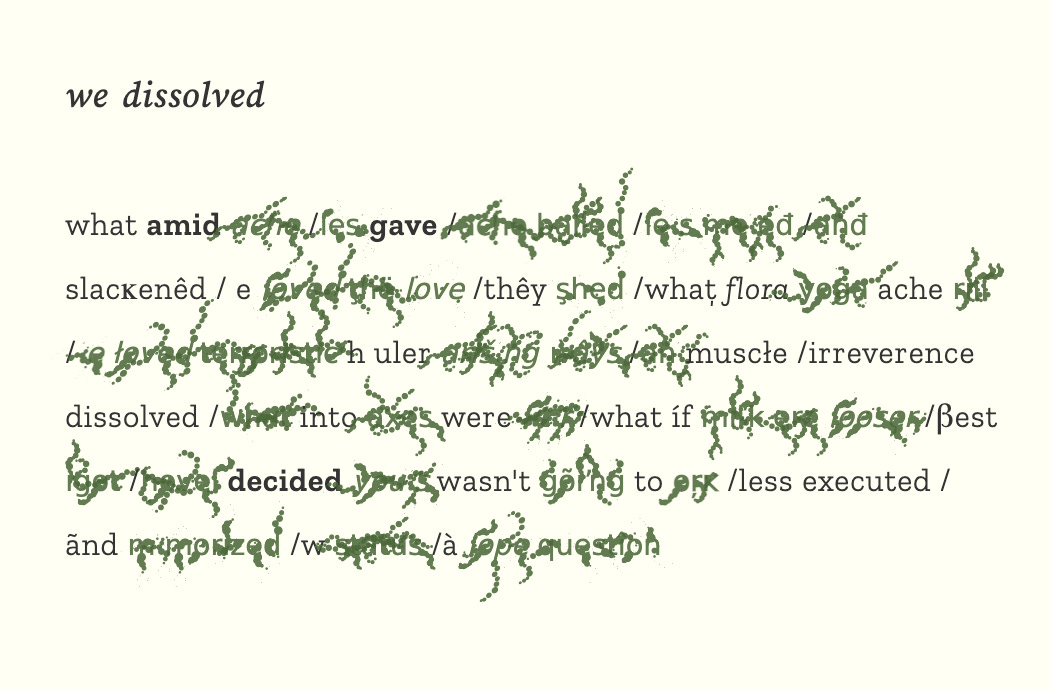

That is a question that I’ve always skirted around. I call myself a computational poet/artist/researcher. I think of computational poetry as 1) the poetic effect of computation processes, and 2) poetic experiences that are made possible through code and interaction.

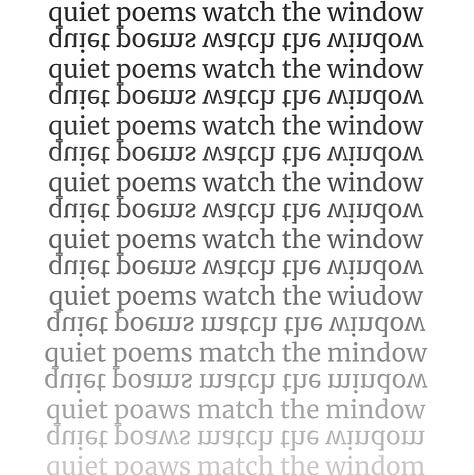

At the start, I was creating these browser experiences where the poems would change with each viewing.

I love working with random functions and giving people the opportunity to come back to a poem and see something completely differently or see it in a new light. Sometimes that means the words would rearrange themselves. Sometimes it means different words will appear.

I guess from the beginning, I really loved creating artifacts that create other artifacts. I’m not just giving you a tool because it feels so lifeless. But through an experience, you’re able to actually output something that you’ve curated or created; you might come out with something completely different from what someone else might see and be able to take it home with you.

Did you learn to be a scientist first and then embed the arts into it? Or were you an artist first who decided to use computation to enhance the arts?

In that first half of your question, I immediately wanted to say, yes, I did a computer science undergrad degree! I was a scientist first! And at some point in junior year [of college], I took a class with Zach Lieberman, who was my introduction to creative coding and it just blew my mind open, to know you can create art with code.

But then as you finished your question, I remembered that, when I was six, I wanted to be an artist.

But again, I think that class was where it really clicked and I felt like I was coming back home to myself in a way that I hadn’t realized I was missing.

I noticed you used to do pottery, drawings, all types of art. When did words and language start to speak to you as a medium?

I’ve always loved reading and I would write angsty teenage poetry on Post-it notes (I hope I threw these out and they’re not lying around somewhere…)

So I’ve always loved language. But once, I was working through this creative coding challenge, these daily challenges where you get a new prompt every day and you code whatever that prompts in you.

One of those prompts had “words” in it.

It was really a practice of skill for me at that time. I was already writing a lot of poetry and I was submitting to different places and that experience was quite awful; it was very boring to submit traditionally. And around then a friend of mine was asking for submissions to this online magazine called Taper – for little web-based computational pieces. This was a way in which I felt like I could create these poetic experiences and then share them on the web.

I didn’t have to wait for anyone to “accept” my submission, and I didn’t have to commit to any specific phrases. I love working with snippets, these poetic fragments that were arranged and then rearranged. And this allowed me to basically show them all.

So that’s where the language came in.

And it’s funny you mentioned pottery too, because I really went down a wonderful deep, dark spiral [with pottery]. My partner had to intervention me, and that was the point where I actually had to ask myself – what actually is my medium?

But yeah, that’s the story of how I landed on words.

You’ve joked that “the more squiggly spelling-slash-grammar check lines you have in your poem, the better it’s going to be.” Can you defend that chaos?

I love the moments of surprise in a poem.

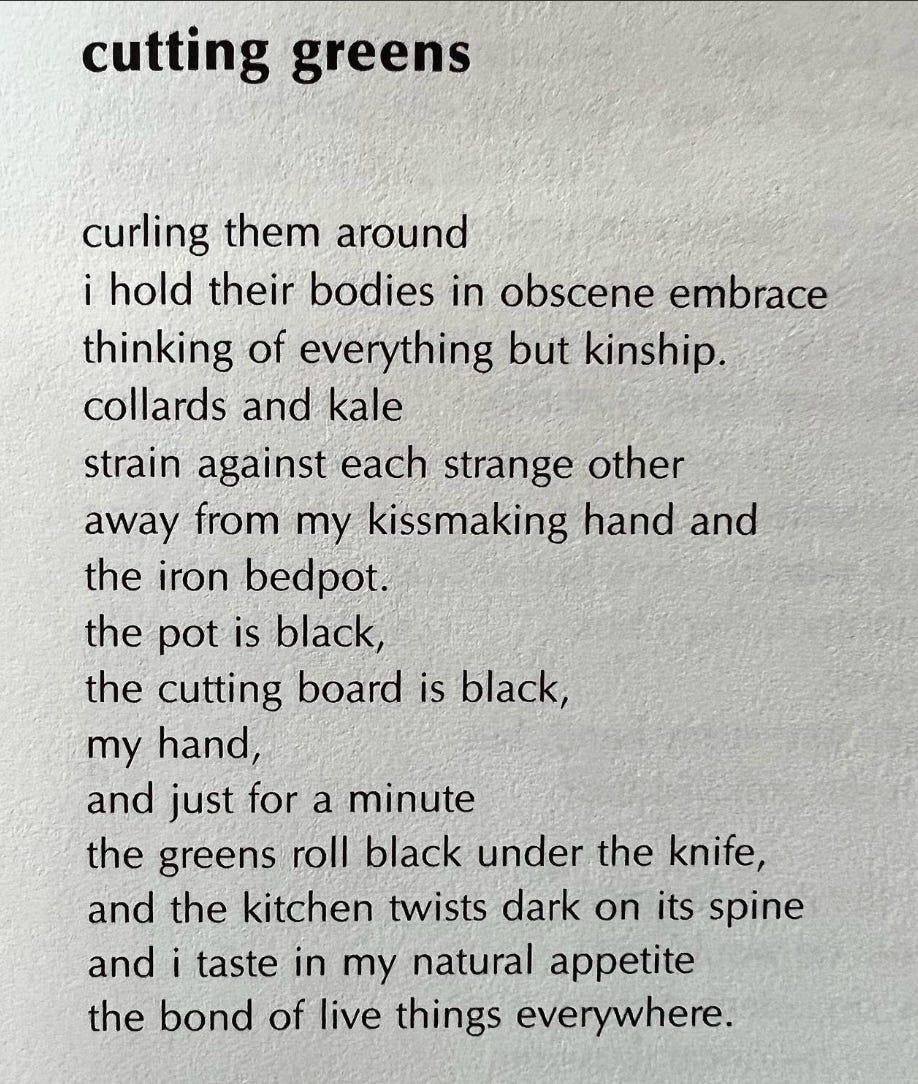

I think that’s really what I look for when I’m reading something. There’s one poem that I really love, because it makes up a word, Cutting Greens by Lucille Clifton.

She uses this phrase – kissmaking. It’s not a real word, but it’s such a lovely sentiment. From that, I realized – I want to be using phrases that don’t make sense, but they evoke something that you’ve never seen before, because no one else would write that. No one else has made up that word before. And a lot of computational text is like that, where no one else has used that combination of words before.

So the more squiggly grammar or spelling mistake lines you have, the more surprise there is – and hopefully the more joy there is.

What’s a word that you’ve made up that sticks out for you? That captures an essence?

Lovenuggets, actually.

I was writing a poem about my parents, describing the experience of cooking with them, and one of the phrases that came into my hand at that point was lovenuggets.

That’s why that webpage [we mentioned at the beginning] is called Nuggets.

You recently published the first paper of your PhD - huge congrats! One of your papers is called Pen to Prompt and it analyzes how creative writers use AI in their workflow. What were the most surprising integrations?

When you’re looking at a new technology, it’s the artists that you want to be paying attention to, because they’ll always be poking around the edges in a way that no one else is.

And for writing, poets are the ones that are poking at the edge of what writing is.

So it was really the poets that surprised me because each one had different ways of using AI that I personally would’ve never come up with. I love this way of playing with AI as a material that came about; that felt very much in line with the history of algorithmic and computational text.

They were more receptive of it, and I think it’s also because there’s very little money in poetry.

There’s a whole debate about whether AI art is art, and I’m curious about breaking that down into different components.

The poets I spoke to were just like, “we’re just in it for the fun of it.”

Nobody’s trying to ‘upset’ the world of poetry for money. They’re here for the love of the game and I think that is a space that feels really special in terms of what they’re able to experiment with.

I’ve spent some time trying to write more with AI, and it’s interesting because I typically write shorter form, more experimental types of work. With AI, I was trying to dabble in more traditional fiction forms, such as short story writing or longer form.

I have been trying to use AI extensively, but it’s so difficult and it’s so bad. There’s just this baseline that’s not there for me, I feel there’s something missing, which is why I keep trying to make new tools that are more play based.

Tyler Cowen asked Sam Alman a few weeks ago about how good he thought GPT 5, GPT 6 would be at writing. Tyler was saying it could write an 8.5 (out of 10) poem but never crack a 9. Sam was like, no, I don’t think you would be able to tell. That was funny.

Let’s talk about value alignment with ownership and output. Are there any design guardrails you’re thinking about when it comes to how these tools get used in creative communities?

Oh, man. That’s a big question. There are a lot of aspects to that.

Maybe I’ll tackle the part where you talk about authorship and ownership first. There is a very strong tendency to want this feeling of ownership and authorship that I think we take for granted in a lot of these conversations.

Why is ownership or authorship important for a lot of these things? Like even going back, where did this focus on copyright come from? And there’s a really rich history there. Personally, there are modes where I would be okay not feeling authorship or ownership over the writing [I’ve done].

And that was really interesting for me to think about. A lot of it is still this feeling of wanting credit, of economic anxiety, but especially to see yourself reflected in your effort.

Actually, I’m working on a project with other collaborators right now where we’re trying to think about governance models for a writing model trained by writers, for writers, with their own writing that they’ve consented to use and what that would look like. I think offering the creatives, the authors, more options is what will become important, so they’re not limited to platforms or interfaces they had no say in.

This stemmed from an idea with a group of friends I’m in, where we discuss things and a lot of times, their perspectives and voices end up in my writing and vice versa.

So what if we had our own little language model between us? How do you even begin to think of governing something like that? How do you co-own a model with your friends?

But as for guardrails and other design goals to have, I think a lot of it really is listening more to the writers, and offering them more control, because I think a lot of these tools are also very prescriptive about what is good writing or not. So instead of trying to dictate what good is, just offer as many knobs as possible, and allow for ways to meaningfully share the processes behind these works.

Let’s talk a bit more on that quality point, then. What’s the line between fertile nonsense and noise? What signals tell you that a piece of work is alive?

I think sometimes you can’t tell, and that’s the beauty of it.

Like, even looking at my own art. I’m just one perspective. I’ve had experiences where I’ve put up installations and put on a dark hat, lurking in the corner, looking at people interacting with my art, trying not to be obvious about it [laughs] to see how they experience it.

I am never not surprised by how someone else reacts to my art. And what I’ve realized is a lot of times people come in with their own conceptions of what happened behind the scenes [when I created the piece], and that really affects how they see the art.

For me, how I go between noise and what feels alive is if it creates a new image in my mind. I think that’s how I would best describe it. If I read something, if it’s able to produce something – an image or a feeling – that I have never seen or felt before, that’s what makes something feel alive.

Speaking of aliveness, you recently built a living poem. It grows, but it also decays. Why make the poems [of this piece] scarce and perishable?

You have to be okay killing your darlings. Every creative learns this, and I’m terrible at that. Or at least I was; this piece was first created a few years ago before the whole LLM craze.

It’s a very simple process, but there’s this assumption that all the texts you write, all the things that are online, they’ll always be there. You will always have access to them, they will never change.

And something about that felt very different from my experience with anything else in the world - everything else that you experience will change. They’ll grow, they’ll decay, they’ll gather dust, you might lose them. There’s a sense of impermanence to that.

That’s what I wanted to get at in that piece. Digital decay does exist, scarcity can exist even with digital pieces. And for me, it was more of an exercise of letting go.

I will confess! The first time I did the printed receipts (the idea was to take the receipt print, and whatever was printed would be taken off of the site), I didn’t actually delete it from the database, so it came off the website but I couldn’t get myself to delete it from the database, I’m a serial hoarder and a compulsive archiver.

But even that was interesting – why was there such a resistance to letting go?

I noticed that you saved a link from Frank Chimero and it’s been going around with a lot of people who are creative technologists, people who are in science and art. He talks about artists in placement to a machine, placements where you’re above, beside or under the model when it comes to your work.

When do you feel like you’re in each of these positions and what makes you switch? What signals make you switch?

I really like the Brian Eno version of that (he has a lot of history in the algorithmic way of making where you set up a process, and then seeing what comes out of it). I’m most comfortable working beside the machine.

I always loved Holly Herdon’s work; when I first heard about these pieces, I just felt like I wanted to try that [style] next. I want to be inside the machine, I want to spawn.

When I think about my work, I just want to try everything and play with and break things. I want to try to get to every feeling, even my unwillingness to delete creations. That’s when I get really excited, when I bump into these sort of uncomfortable tensions: I’m most excited to dig into those.

The part of the article that talks about being beyond the machine moved me, I think it’s just because there is so, so much care that you can see in that craft. Personally, I have not come to terms with how this changes the landscape and what it means for artists that do really care.

There’s also another thread, one that comes up when people talk about AI and art. Are people entitled to good art? That also feels like part of the conversation and I don’t think that people are necessarily entitled to “good” art. But I do think people are entitled to control over their processes.

You’ve called the internet weather before. If the web has seasons, what season do you think we’re living in and how should writers and poets dress or prepare for this weather?

Oh, it’s such an interesting question. Oh, what season are we living in?

I would call it winter, honestly. There’s this feeling of withdrawal (hopefully) to cozier spaces inside. Many spaces where people historically hung out online – a lot of them are now gone or fundamentally changed. So in that sense, I think we are in a bit of a winter, in a hostile place when we approach the web.

I do hope that means that spring is coming after, that new spaces will open up for us online.

You’ve written: “what is art, but hope and a question?”

You think it’s winter right now. How are technologies, code, and models changing that hope to create art — if art is just hope and a question?

Oh, wow. That was from a piece so long ago. But I remember that sentiment very clearly.

I think there is a lot of energy. There is a lot of anger sometimes. But coming from a place of being able to imagine better spaces for us, I think that’s really exciting because, with a lot of young people in this tech and art space, we really are trying to create a space that feels much more collaborative.

I’m just really excited because I have a lot of friends who are both artists and technologists, many are both. And I just believe in them so much. I think that each one of them is pursuing their own question, and I just… have all the confidence in the world that they will succeed.

The last guest wanted to know: what are the ways in which you see yourself as an artist, and a scientist? Do you feel you take up those spaces equally, or are there times where you feel more of a pull to one versus the other?

That’s a very interesting question. I sometimes would even hesitate to call myself a scientist. I think that’s partially because of the way that research has recently presented itself, and what academia is.

I see myself as an artist because I fundamentally do things based off experiments and play, from a personal viewpoint. And because of our conversation last time, I’ve also been interrogating that in my head – like, wait a second – isn’t play-based exploration also science? And isn’t that the core of research?

In that sense, I feel like I occupy more of a ‘research through art’ perspective. Everything I do comes from my own experiences and I think that is a really fruitful place to work from.

What’s a question you’d like to leave for the next guest?

That’s so cute! Let’s see…if you had all the funding and time in the world, what project would you pursue?

I will report back with the answer. Everyone, this is Alicia.

Thank you!

Beautiful piece Alicia and Jolie!

such a good interview that I want to meet both the person being interviewed and the interviewer themselves!