TDSD will be hosting an exhibit of researcher-creatives like Anna in mid-November. If you’d like to support as a patron or sponsor, please get in touch! If you’d like to attend, details to follow.

Anna Matsumoto is a computational artist and HCI researcher who designs interfaces that meet you at the level of the body — where seeing can be done with touch, sound, and motion.

A researcher in product design (specializing in blind and low-vision communities) at Stanford, she builds haptic installations that “break the fourth wall,” turning the senses into a shared language. In our conversation, we talk about choosing the hard path, the beauty of glue and cardboard, and finding community.

Tell us – who is Anna Matsumoto?

I am Anna Matsumoto; I’m a creative technologist and artist.

I do lots of art. I used to paint a lot, after that I loved making things. In Kindergarten, I loved making toys that I saw on TV shows; if my parents wouldn’t buy me the toy, I’d just make it. I’d make toys for the other kids as well.

I just love making things for people and making the world a little bit more fun.

Later in life I learned technical skills like engineering, coding, and soldering. I studied product design at Stanford, which opened my artistic expression even more – to use technology to make creative things.

There are a lot of topics you’ve spoken about, like access to education and women’s empowerment. How did you decide to make accessibility the focus of your art?

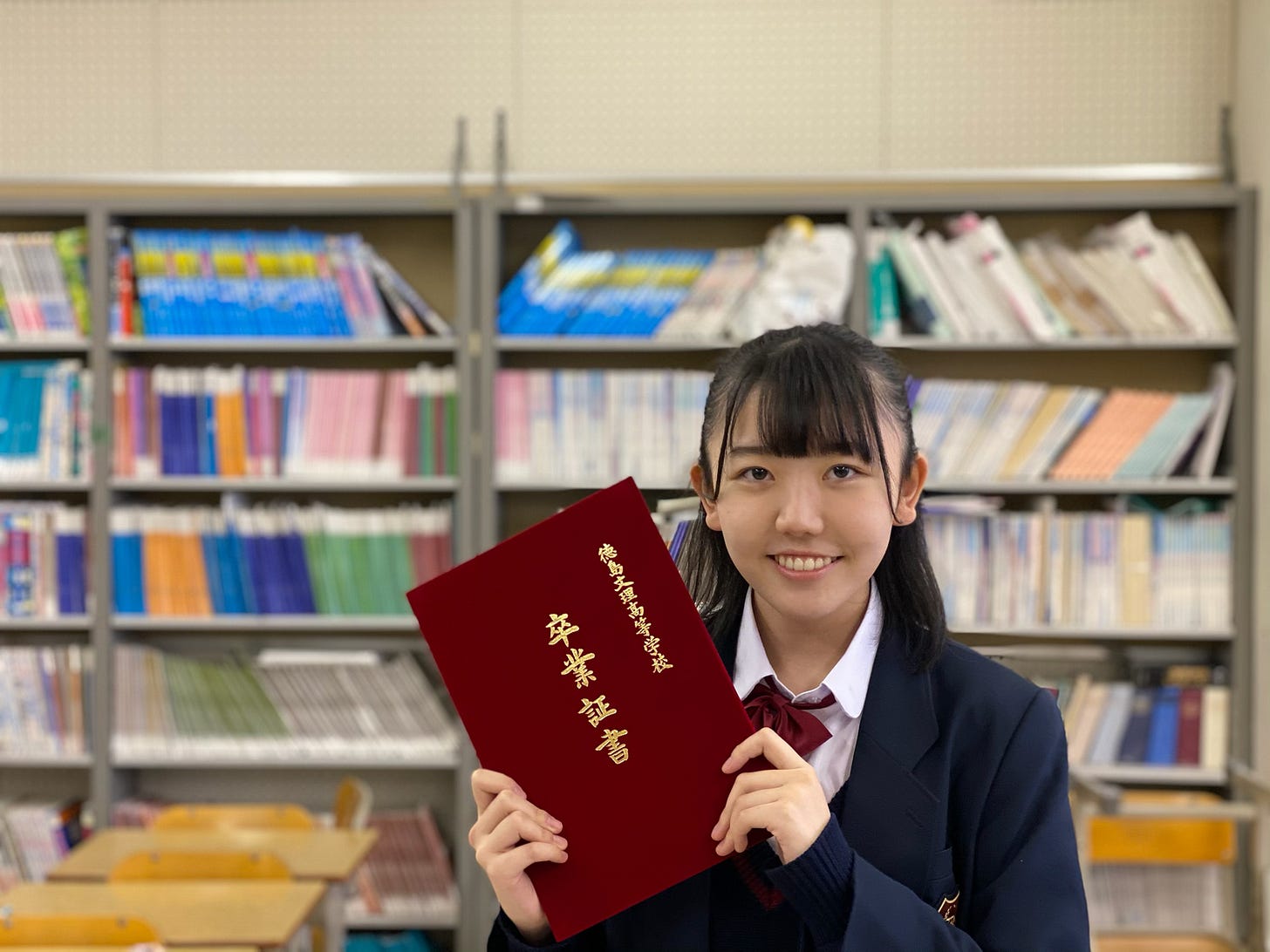

When I was in high school, I loved making things, I also wanted to make the world better. Once, I was in a project doing several interviews in my hometown in Japan [Tokushima], and spoke to one teacher who was teaching at a school for the blind.

She talked about what it was like in World War II, and how hard it was to evacuate a blind school. I felt the hopelessness (I’m not sure if I’m saying the correct English word) in her words. There was this feeling that, if you were born in a particular way, you needed to just accept your fate.

I didn’t like that. Japan’s a place where the world’s biggest earthquakes happen, it has many geographic faults, so we’re also definitely going to get tsunamis – how is everyone going to get to safety? There are so many problems, and in my hometown, the biggest shock was often these accessibility issues.

After that, I got into the research program at the National Institute of Informatics. All the other participants were coding experts. I had no experience, and felt a lot of pressure. But I had one mentor who was doing HCI – and then he really emphasized the importance of having a goal, having a problem statement that you wanted to work on – and that was the strongest factor, not just the skills someone had.

That gave me confidence. I wasn’t a top programmer, but I had this problem statement in my mind, something about the world I wanted to change. So that gave me hope for pursuing more engineering.

The other side of this is where I grew up. My hometown is the only prefecture with no trains in Japan. We’re not connected to other places. We are really limited with resources – and I didn’t realize this until I went to Tokyo and noticed that something was off (in my hometown).

My math teacher in high school had once said that girls just weren’t good at math. That boys needed to teach girls.

My physics teacher said that girls shouldn’t pursue engineering majors in college because we lacked power, like physical power, manpower.

I didn’t even realize it was a problem, until I met some other students from Tokyo, who had gotten good education, and they were so shocked at my story. They asked – “are you living from 100 years ago or something?!”

That’s how you got started with the activism, speaking. When did you decide to exhibit and put your art out as a medium?

In my hometown, it wasn’t a good thing to be doing art if you were studying. I liked studying and my grades weren’t bad, so everyone was like, no, no art, don’t draw, don’t paint, don’t do the crazy thing.

I used to draw a lot of eyeballs. And people would tell me – “that’s cursed! Don’t do that!”

I did stop. But after a while, I revisited it and started this one work that I named Ozone Hole. I started to paint with Sharpies (I was broke and didn’t have nice paints).

I mixed them with alcohol, hand sanitizer. And then also other like transparent pens,

Yeah.

The inspiration from this came from my geography class. I learned about the ozone hole. If you keep releasing human-made chemicals like CFCs, keep polluting the world, you’re going to get a hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica.

I saw that image and I was like, oh, this is bad. At this point people were doing [climate] activism online and I already knew that. But then I was always thinking, we post about it [on social media], but then people who engage with that are already interested in climate. So it’s just in the bubble.

And I wanted to reach people outside the bubble. I was wondering: how can I get them into this field? How can I make them listen to me?

I realized I have the power of art. As I looked at the image of the ozone hole, I said, okay, this is the eyeball; this is our ignorance.

It took me two years to paint this piece because I was hiding my painting from my parents, and could only paint when they weren’t looking.

After some time, there was one exhibition called Monster Exhibition. I loved their concept. So I submitted my work to that when I was in my senior year in high school. It was an international exhibition, so if you got in, you could exhibit in Paris, in Tokyo.

And actually I got accepted as the youngest artist, I think I was 16 or 17 (I forgot) when I got in.

I remember I took the leave of absence from school for a week, I flew to Tokyo, and that was the first time I exhibited my work. I just loved how everyone was observing my work, analyzing it, and trying to understand what I was saying.

Art is my voice. I couldn’t find any other way to express that.

After that I got into Stanford. There were so many makerspaces! It healed my inner child.

Stanford has everything, all the glue, all the cardboard that my parents wouldn’t allow me to have in the house. And then through making things in engineering classes, I realized engineering was also part of the art. So I started to integrate more technology, like AR, into the artwork.

How often do you ship a new piece of work?

Back in college, I would ship at least 3, maximum 20, projects in one quarter.

Wow.

It was crazy. One quarter is 10 weeks.

At first a lot of the pieces started as school projects. But I took them so seriously. I was in the makerspaces until 4:00 AM. I don’t even understand how I did that, looking back, and in my second language.

At first, I was so scared to show my work because I knew that there were so many talented people. But my friends’ reaction to each piece – they reacted like I made history.

And then I started posting, and kept posting, and as I posted, more people reached out. And then I say yes to every opportunity I get.

And you’re still functioning.

I owe it a lot to the people I was around. In junior, senior year, I was in a lot of group projects in class. During my freshman / sophomore year, if the English was too hard, I would stare at my friends and they would paraphrase [what the professors or textbooks were saying] for me during the class.

So many of my peers understood my strengths, and really tried to, how do you say it? Respect my strengths. For example, I was really good at prototyping. But then when it comes to writing, I struggle.

So my peers knew, and they would say, “Anna, it’s okay, you can be the CTO, you do the technical side.” And that helped me a lot.

I spent so many hours working. I was tired, but kept going – actually, it’s because I love breakfast. I never skip breakfast. Even if I’m late to class, I need to eat breakfast. But that meant I was always up before 9:30 am, and I would do my projects throughout the day.

There were many days where I had to spend hours stuck in a room, debugging. For example, with the AR work, I could only debug onsite – like I need to physically be there to check if the visuals come up when I scan.

So I needed to do it during the daytime. So I would go there in the morning when nobody was there so I didn’t look creepy when so many people were around.

In senior year, I was on crutches, but I was still trying to get the AR piece up – so I looked crazy; I was on crutches, wearing sunglasses, and kept scanning a bunch of places around campus. People thought I was insane.

On the language of languages – it’s obvious you’re fluent in many languages of code, of mixed media – like Raspberry Pi, Blender. (I hated learning Blender. Sorry.)

I want to ask you about haptics as a language. What do you think haptics can communicate that pure photos or images or sound can’t?

Perfect question. I think haptics is love.

In Japan, we don’t really hug. In the US, when people express their love, it’s a physical language.

I made this first prototype to react with audio. I detect the audio information from the microphone of the computer and then I calculate the audio data on Touch Designer, and then generate the parameters and then send it to Arduino. Then the balloons, seven balloons interact with the sound. Boom.

I first brought the prototype to a party, where so many people actually gathered and just put their hands on the glowing balloons. Although they weren’t talking, they were just closing their eyes, those 5 or 6 people were sharing something, sharing a space, an experience.

You generally have solo experiences in art, even in interactive exhibits. But with haptics, there’s a shared experience.

Do you think that haptics, do you see it as like a language where you could have symbols, metaphors, and representation? Or is it more like music, a sound element of its own, a feeling, emotion, composition? So do you think of haptics as both, or one or the other?

Good question. It’s a yes for both, let’s start talking about language.

My lab’s name was the Stanford SHAPE Lab. We worked with shapes for blind low vision (BLV) and visual accessibility. I was exploring tactile maps and 3D printed educational resources and so on. My focus was assembly and its instructions.

Which means if you have a complicated topic, like molecules, or bone structure, to explain those to people who are BLV you need a hands-on experience.

How do you explain the order of the structure, or how to assemble things without visuals? It’s actually really difficult - let’s say you’re describing bones in the wrist, neck; if you can see it visually, you can say, oh, this part is the fibula, and it connects to these other bones.

But if you can’t see it, maybe you tell them, oh, it’s a square-ish kind of shape, but it’s so hard because our working verbal memory, what we retain by listening, is limited.

If we don’t have visuals, how do we support them? So that was my focus. I added tactile icons [squares, triangles] onto our models through user studies with BLV subjects.

Then I asked myself: how can I also use those strategies in my art? How can we translate that feeling into a touchable thing?

Has this direction of your research changed some beliefs you had about accessibility before, and how has it changed the direction of your art?

When I was in Japan, I saw so many technologies and thought, “oh, this device is definitely going to change the future.” But the user is niche and generally a minority. They’re not going to pay an expensive amount for technology.

But if the researcher can’t make profit, that’s not sustainable. So a lot of great research and products disappear after 1-2 years.

With art, I don’t have those same constraints. I can let everyone, whether you can or cannot see, it doesn’t matter as long as you can touch. That experience with that artwork doesn’t go away. I can reach even more people in a really accessible way.

One of the observations I made as a viewer of your art is that there’s different ways I can interact with a piece. Sometimes you use the body as a medium – like interactive pieces. Sometimes the person or the body part is the subject – like the drawings and paintings of eyes. And then the third thing is the body as a method, like with haptics that breaks the fourth wall. How do you decide when the body is the medium, a subject, or the method?

I love that question.

I first started with 3D animation, visual performance audio, interactive visuals. I wanted to put that into a form that a human could interact with, not just audio data.

The first piece was one where, the more you danced, the bigger the visual and sounds got. I wanted to add more senses, to tie art into the physical world.

My second work was with my friend, and we incorporated all the senses – we put out a bitter melon, a heater, a hologram, and a candle in a space, so it covered smell, temperature, taste. So we just explore all the senses.

Then I wanted to do more active interaction. That’s when I did more work with bodies – I had a friend wear an EEG reader, I wore a ring, and we controlled each other’s movements and sounds.

Through all of these projects, I learned how to model 3D things, to create 3D animation, and how to use motors. I experimented a lot. That’s why I’ve been using different media, different interactions, creating different worlds.

One of the things I love most about our generation, and the new dimension that science is moving into with art, is how engaging it is. There’s not an imposed hierarchy that older artistic waves normalized.

It’s a dialogue. I’ve always thought of art as a dialogue. I’m telling you something through my work, and that message is true over time. Even if it’s five years later, even if I exhibit in a different country, we have dialogue.

There’s still a few questions I have for you – but I realized, the reason you felt so familiar to me [Jolie] is because every year, for the last 5 years, I’ve bought a Hobonichi notebook (it is the best paper to write in. Brilliant paper engineering). I read the daily quotes, and there was one day where you were quoted!

[bows over laughing] Yes! June 24th, 2024. And also like March or December sometime.

I bet you didn’t expect me to dig this up, but if I remember correctly, you talked about hope. We’ve talked about the challenges of being a 22-year-old, independent artist and researcher. Could you tell me how you’re feeling about hope, looking back at your journey?

[laughs again] I wasn’t expecting it at all, that someone remembered it!

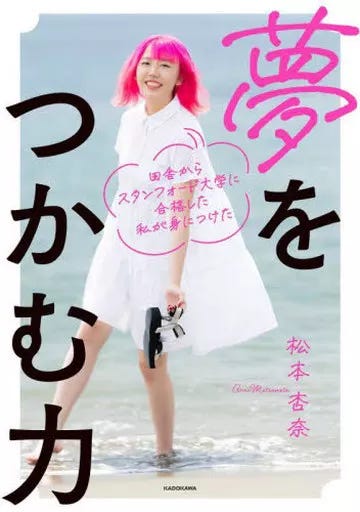

I wrote a book in Japan in 2022. It became a bestseller on Amazon. It’s called The Power to Seize Your Dream.

I was born on Tokushima in Shikoku Island, it was in the middle of nothing, no hope. I never thought I could do the things I dreamed about.

As a kid, I watched so many Disney movies…they all say that if you believe you can do it, you can fly. And at some point, I thought, “okay, let me just try once.”

Since then, I’ve just kept trying. That’s how I started studying English. I thought to myself, okay, let me just try studying English. Let’s see if I can get better. If I get better, I’m gonna do more. I’m gonna start talking to American people online or something.

And then my English got better. Then I thought, maybe I can go to the USA, if I can get a good score, I could go to a university in the US.

I took the SAT exam. It was shit. The score was terrible. But then I took it again. And then I just kept doing it and then I just kept promising, trusting myself. That trust gave me confidence. That confidence gave me more hope.

I think at the bottom of my heart, I never believed in that hope [at the time]. 80% of me thought it was impossible. I just lied to myself, almost brainwashed myself into believing I could do these things. But that’s why I needed to keep going, to get to where I am now, where I truly do believe in that hope [now that I’m older].

Second to last question comes from the last guest. How do we better coordinate as researcher-creatives? How do we get everyone together?

We have to keep creating. If it’s just technology, it’s still in the bubble. There’s a really good word in Japanese – 使命, Shimei – let me translate, it’s the mission, the mission we have as creative technologists is to translate that technology into a form that connects with people, creating an experience. Science communication. We connect through technology, and it’s our job to connect people with creative technology.

I’m going to ask you to pay it forward, to leave a question for the next researcher-creative.

Who are the people you want to bring these technologies to? What do you want to translate through technology to people? And why?

Who are you trying to bring this to? What is your purpose?

This is something I learned doing product design - it’s about understanding the users. And I took this seriously. Once I needed to do a study for a fitness trainer, so I went to Barry’s three times a week. I was in the session, taking notes while running, the trainer would yell at me – “Anna, keep going!” – and I’d keep going. I did this with SoulCycle, everything – interviewing the attendees to understand their needs.

I got a B in that assignment! I went to Barry’s three times a week!

And that was because I learned it’s not enough to interview. People will never tell you what they need – you need to feel and analyze.

You’ve done it really well. Obviously your art touches people; I’m very glad you’re my friend. Anna Matsumoto, everyone.

That warms my heart up!

Lovely interview! Thanks for sharing Anna's work, checking it now 😊

Wow, these pieces are incredible. I can only imagine how many hours of work go into each one - the code and the soldering are hours on their own.