Oh, to be a new grad in 2025.

I’ve just wrapped up my degree, splitting my final year between Toronto and Boston. Since leaving both cities, I catch myself missing the dense galaxy of campuses, the way a cheap bus ticket and a spare couch could send us sprinting back into the makerspace with a brand-new idea.

These memories are a reminder of what a university can be at its best – a concentration of talent, curiosity, and argument within a 2-kilometre radius. Yet this same year has also sharpened my frustration with what higher education often feels like now – awkwardly dangling the freedom it once championed.

I explored my own tension with higher ed in an earlier piece, “To What Degree?”, but still wondered:

Why did societies fight to protect these institutions through wars, depressions, and political upheavals?

What core functions made a university historically indispensable (and relatively independent), even when it opposed political power? How did we lose that?

Where are young people turning to, and what shift in values does this indicate?

What follows is a reminder of what the university was designed to do, how those purposes evolved, and what they still represent today.

Universities Before “The University”

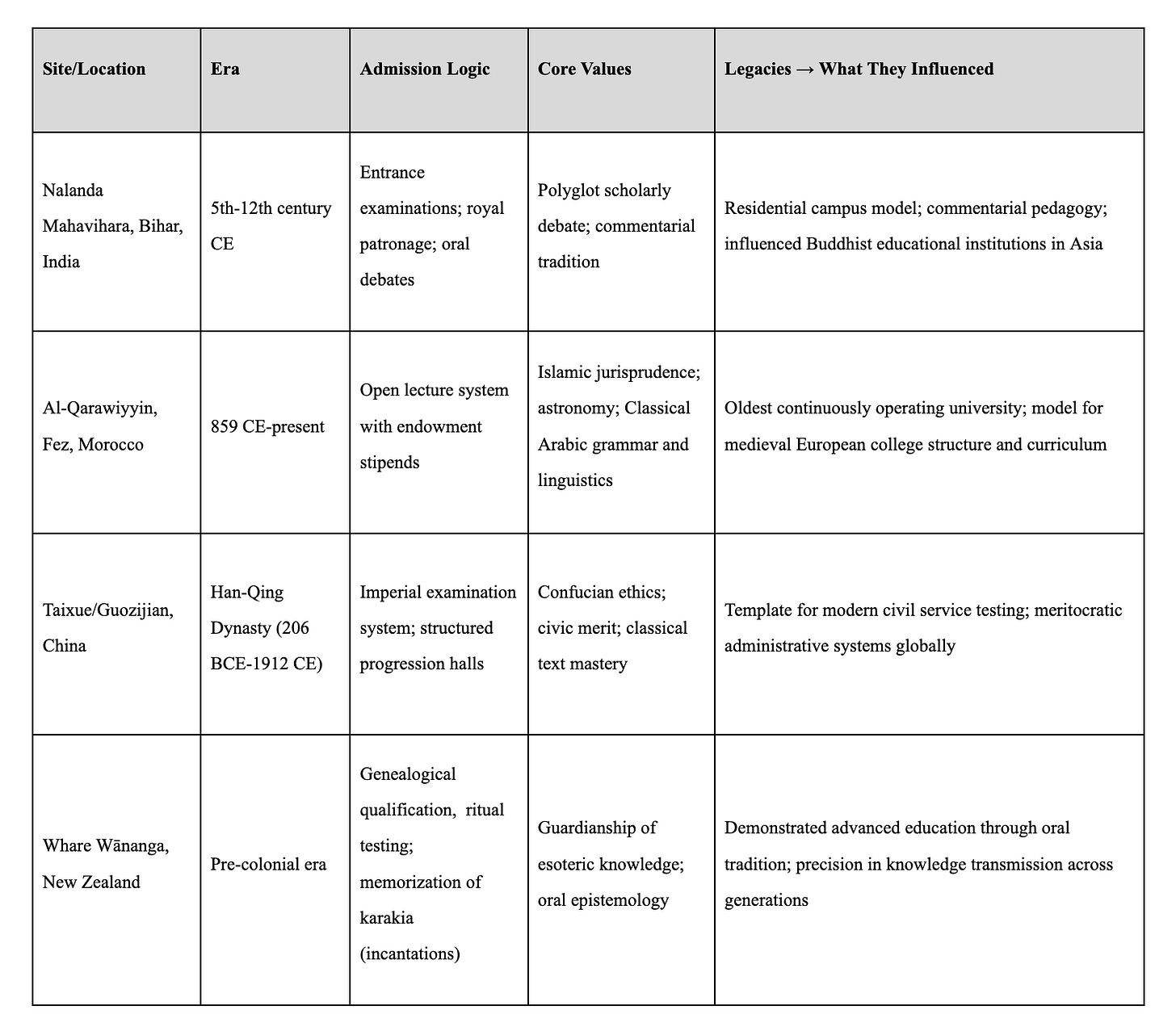

The modern university system, with its structures of faculties, degrees, and campuses, emerged in medieval Europe around the 11th and 12th centuries. However, long before Bologna's founding in 1088, knowledge guilds existed across continents, sharing some common DNA: the preservation of knowledge, selective admission processes, and ritual communities that legitimized each new generation of interpreters.

The Foundations of Discourse

The creation of the modern university is the product of time-stampable “pivots.”

First came the medieval guild school, crafted from a “bottom-up” approach. The University of Bologna was the result of several students who formed associations to set teaching goals and oversee their implementation. Professors were hired directly by student guilds, and the relationship between teacher and student was more like a craft apprenticeship, where knowledge transmission occurred through personal mentorship.

Medieval universities operated on principles that would seem revolutionary today. Students enjoyed extraordinary privileges, including freedom from taxation and military service, and from arrest and trial in civil courts in some cases. More importantly, they possessed what we might recognize as the earliest forms of academic freedom. Collective associations of teachers and students banded together to protect their rights and privileges, set standards, and resist unwelcome interference. When authorities threatened their independence, universities deployed their ultimate weapon: the right to strike and suspend all lectures, first granted to the University of Paris by Pope Gregory IX in 1231.

Creating the Research University

Wilhelm von Humboldt’s 1810 Berlin reforms fused teaching with original research, casting knowledge as an open-ended pursuit and giving professors institutional autonomy.

By the 18th century, the university was constrained by nepotism and class privilege. The Humboldtian model combined scientific knowledge (research) and instruction in a single institution: this viewed science not as something already found but as knowledge that will never be fully discovered and needs to be searched for unceasingly.

The new model flipped the professor-student relationship from medieval apprenticeship to modern academic mentorship. Students were no longer guild members hiring teachers, but rather apprentices in the pursuit of advancing human knowledge. The university became based on unbiased knowledge and analysis, combining research and teaching while allowing students to choose their own course of study. This created the template for what Johns Hopkins University president Daniel Coit Gilman would transplant to America as the first true university, in the modern sense, of the United States.1

Enduring Remnants

The campus is an enduring arena. Through plagues, religious schisms, national revolutions, and two world wars, it has absorbed value shifts without fatally collapsing, even when internal ideas clash. It is a sacred balance of institutional immunity for dissent (which enables critique and innovation) and intellectual renewal through turmoil (each significant crisis spurs, or should spur, substantive reform).

We tend to forget that Martin Luther held his chair at Wittenberg when he nailed his Ninety-Five Theses; Galileo’s heliocentric lectures at Padua helped pry science from scripture; students at Peking University ignited the May Fourth Movement in China; half a century later, anti-apartheid protests at the University of Cape Town pushed desegregation.

Protest is one safety valve, but disruption doesn’t have to be loud or angry. Much of what still makes a campus transformative happened in quieter, slower circuits first forged centuries ago:

The Journal. From Islamic ijaza chains to The Oxford Gazette (1665), journals began as low‑stakes noticeboards for speculative claims to gain traction, revision, and collaboration. Before peer review existed, this was a way for budding scholars to test their ideas.

Viva Voce & Tutorials. Oral disputation that trained Bologna’s jurists now resurfaces in PhD defences and Oxbridge one‑to‑one tutorials.

Residential College. From Nalanda’s cloisters to Cambridge courts and now ‘dorms’ and ‘quads,’ dense living-learning layouts create more serendipity (‘happy collisions’) among scholars.

Waqf → Endowment. Charitable trusts that bankrolled medieval madrasas preceded today’s university endowments, underwriting research and need-blind aid to continue supporting the next generation of thinkers.

Even when lecture halls teemed with heresy or protest, societies – including those governments and leaders that may have opposed the institution’s ideas – fought to preserve the university because the campus served functions that no other institution could match.

First, it was a strategic reservoir of expertise: monarchs needed jurists, industrialists needed engineers, Cold War states needed physicists. Second, it was a neutral archive and testbed for ideas; papal bulls, royal charters, and later the GI Bill all safeguarded scholars precisely so they could criticize church, crown, or congress without dismantling the knowledge factory itself. Third, it was a talent magnet and legitimacy signal: founding a university announced a polity’s seriousness about the future.

Historically, even pragmatic politicians accepted the occasional disruptiveness of independent scholars, recognizing that allowing them free rein paid rich dividends in technological innovation and effective governance over the long run.

Donald Braben, Scientific Freedom The Elixir of Civilization

How the Covenant Frayed

For centuries, the university maintained a (occasionally) shaky but functional truce with power: rulers paid the bills and largely stayed out of the lecture hall so long as scholars kept at it for the long-term game. That truce frayed once modern states began treating campuses as instruments of national strategy and cultural signalling, arguably around the mid-twentieth century.

What emerged is a subtler form of capture (or coercion): incentives that coax scholars to trade their autonomy for funding, patents, tenure. Four pressure points briefly illustrate the cracks in the glass:

Cold‑War Compliance Culture. Post-1947 mega-grants came with required milestones and reporting mandates; autonomy was traded for scale.

Bayh‑Dole & IP Capture (1980). Tech‑transfer offices steered agendas toward short‑termable patents.

League‑Table Managerialism. Rankings compressed reputation into metrics; administrators optimized what they could measure.

Political Encroachment Without Protest. UK research councils' prior-approval regimes were passed “without a whimper,” effectively undermining self governance that once guarded curricular and research freedom.

What We Value Now (an Alien Audit)

For a millennium, the university has served as the society’s seismograph for whatever we value most: scholastic liberty in Bologna, focused research in Berlin, and national prowess in Cold War America. If that pattern holds, our universities now are a real-time forecast of contemporary values. What does our current situation reflect now?

The UK Grading Paradox

Over coffee, I was reminded that in Britain, a “First” normally begins at 70 percent. Anything higher is exceptional but unnecessary for distinction; the more common 2:1 bracket (60–69 percent) leaves headroom to take intellectual risks. The doctorate is still styled a DPhil, signifying an apprenticeship to inquiry rather than a single discipline. I think that’s beautiful.

That tolerance for imperfection is baked in long before university. British students generally sit only two national assessments, GCSEs at 16 and A-levels at 18, giving them some years to experiment with ideas and writing styles without the drag of term-by-term GPA arithmetic. North American students accumulate numeric scores (often on a 0-100 scale) every year from kindergarten onward; a 4.0 has become the hard currency of scholarships and internships, rewarding strategic obedience over audacity.

Might the university on the Cherwell outlast its cousin on the Charles?

Where Youth Are Turning

The last great reinvention of higher learning – Humboldt’s research university – was sparked by students and scholars who judged the 18th-century model intellectually dead. We may be at a similar inflection: the talent flight we see today is a market test of the university’s monopoly on time, money, and meaning. While most high school graduates still pursue a two- or four-year degree program, a significant number are choosing alternatives worth paying attention to.

Two patterns stand out:

Decentralisation. No single rector or state charter decides the curriculum; new entrants spin up as quickly as open-source projects or donor-backed fellowships.

Iterative experimentation. Multiple models now run in parallel, each probing a different failure mode of legacy higher ed – cost, visa rigidity, credential drag, or risk aversion. When dealing with a complex system that has multiple manipulable variables, employ the scientific method and adapt accordingly.

What follows is a brief series of observations I have noted from five prominent alternatives (plus the early rise of independent PhDs, which I have kept separate because the others are oriented around undergraduate equivalents). For each, I sketch what they preserve from the old covenant, what they discard, and the fresh risks they introduce. All this to say - it’s possible to reinvent the wheel.

These shifts and risks aren’t necessarily bad! History shows that academic stagnation precedes renewal. Today’s systems will likely play the same rejuvenating role, provided we treat it as an ecosystem to learn from, not a winner-take-all replacement.

Talent flight is an X-ray of value drift: autonomy and throughput now trump continuity and memory. Decentralized models lower the cost of entry, diversifying who builds curricula. Iterative pilots surface real-time error signals, allowing us to adapt before they soldify.

What will be different about the next educational landscape is that it is unlikely to be one monolithic heir. Maybe future students will get an educational index fund: the opportunity to experience multiple options as they arise, each “solving” a different element that the campus currently balances in a single place.

The question is not “which model replaces Harvard?” but “which combination of models preserves intellectual slack, respects lessons from the past, and can still surprise us with the next Martin Luther?”

The Independent PhD

The Independent PhD has intrigued me for about a year now. Two examples I frequent are those of Andy Matuschak and Nadia Asparouhova. Andy funded his research on cognition-augmenting “tools for thought” with hundreds of small patrons, not grant panels, letting him publish notebooks and prototypes in real time rather than chase journal acceptances. Nadia argues that curiosity, public writing, and direct patronage can replace formal committees and campus funding; she built a “personal assemblage of learning,” producing a public report on open-source economics, delivering conference talks, and securing fellowships—all on her own terms.

Both models preserve the university’s oldest virtue - radical autonomy for long-horizon inquiry - while discarding credentials, departmental politics, and overhead. The trade-offs mirror the broader patchwork above: they gain speed, audience feedback, and topic freedom, but risk isolation, laboratory inaccessibility, and income precarity. Some questions of mine remain around training, building community, accessibility (especially to younger researchers without significant professional experience or financial nets) and practicality in select fields (such as the life sciences), but I’m excited to see this model evolve.

But…Here’s What We Risk Losing and Why it Matters

The adaptation of new models is healthy, but not cost-free. Three functions that universities long protected now, despite fluctuating success, sit on a fault line. In most of these new experiments, there is limited evidence that these will be prioritized, let alone preserved.

Written synthesis as a civic craft.

What it was: From Erasmus’s Latin epistles to the 70-per-cent “First” at Oxford, writing well enough to persuade a skeptical peer group was treated as public service, not résumé garnish.

Why it’s fading: GPA inflation and point-and-click assessments reward speed and compliance; boot-camp rubrics measure runnable code, not argumentative clarity.

What we lose: Citizens who can trace a contested idea (not just code) from premise to consequence, and change their minds in print.

A commons dedicated to opposing, but respectful, speech.

What it was: Universities maintained designated arenas where the most contested questions of the day could be cross-examined before a live audience. Think of the Oxford Union, where everyone from Malcolm X (1964) to Marine Le Pen (2015) has faced open rebuttal; the weekly tutorial disputations at Oxbridge that require students to defend essays aloud; or student-run “great debates” at Hart House in Toronto and the Chicago Society, which still invite ideologically opposed faculty to spar in public.

Why it’s fading: Online echo chambers let us curate away disagreement, while on-campus disinvitation campaigns make institutions risk-averse; many alternative programs (boot camps, DAOs) lack any built-in forum for adversarial dialogue at all.

What we lose: a space where clashing world-views meet shared rules of evidence, training citizens to argue, listen, and occasionally change their minds.

Long-horizon laboratories & archives.

What it was: Universities have always sheltered projects whose payoff lay decades, sometimes centuries, away. Two of the most durable formats are the research laboratory and the scholarly library. Cold Spring Harbor (1890) still pursues open-ended genetics; CERN’s Large Hadron Collider took almost 30 years to build; the Warburg Institute’s library preserves texts rescued from Nazi Germany that no startup would bankroll.

Why it’s fading: grant panels now favour “shovel-ready” deliverables; tech-transfer offices monetize near-term patents; bootcamps and DAOs are unlikely to budget for climate-controlled stacks or multi-decade beam-lines.

What we lose: the infrastructure that lets civilization remember, re-test, and recombine its deepest knowledge stores. No venture fund will underwrite a Sumerian lexicon or a 30-year particle detector. Without clear evidence that laboratories and libraries will be prioritized in the post-university patchwork, the intellectual slack required for the next CRISPR, or the next Principia, is already at risk.

Relighting

Universities have always been more than factories for credentials or launchpads for careers. At their best, they serve as society’s memory palace, testing ground, and early warning system.

Those functions were never guaranteed. They were protected, generation after generation, by people who insisted that curiosity deserved its own jurisdiction.

The unity is unravelling, but with some deliberate counterweights:

Re-wild the journal. Fund slow-burn, post-publication venues and judge them in five years, not five weeks.

Re-normalize oral argument. Make viva voces, small-group debates, and public defences standard across every discipline.

Rebuild slack. Endow laboratories and libraries whose review cycles outlast any grant officer’s tenure.

Re-fortify the commons. Tie public money to open-speech charters, and enforce them.

We can keep the best parts of historic scholarship alive.

Harvard was founded in 1636 and was the first 'university' of the United States; however, it was founded to train Puritan ministers. Students followed languages of studies that were prescribed - Latin, Greek, Hebrew - the first "true research university" that taught scientific research was established in 1872 - Johns Hopkins. It was the country's first research-based, graduate-level university.