The Digital Architect

How Spencer Chang engineers playful, intimate software for Our Internet.

TDSD will be hosting an exhibit of researcher-creatives like Spencer in mid-November. If you’d like to support as a patron or sponsor, please get in touch! If you’d like to attend, details to follow.

Spencer treats software like civic space — something we co-steward, not simply consume. The question beneath it all is grounding: what shape do we want technology to be? What might it feel like if it were ours: soft, playful, and neighborly?

From “Computing Shrines” that only awaken when you offer your phone, to games and protocols that travel by word-of-mouth, Spencer builds tools that privilege care over scale and agency over algorithms. We talk about communal stewardship, graceful decay, and why technology should sometimes be squishy — something you can hand to a friend, reshape, and make your own.

You wrote about how you’re imagining these features of computing tools in communal agency. They’re community owned, small scale infrastructure. What does it feel like in a product or space and what do you think would betray that communal agency?

Ooh, a hard hitting question. I think it’s a ‘you know it when you see it’ sort of thing. I think everyone, when they’re on Instagram or a large social platform, distinctly feels like they’re on an adversarial environment.

And I think there are other platforms where you can see and feel the care from the people who made it. Intention comes through, and the feeling you get, it’s very hard to describe.

You’re looking to build technology that optimizes for community and not necessarily optimize for scale. Are there any mental heuristics or grounding frameworks that you use in your building to nurture more community? Is this different from when you were in your engineering job?

There is a lot of overlap in how I think about it. In art, you have to think about scale in terms of global reach or, even just the fact that you can’t handhold someone every time they touch the piece.

So I think in that way it’s very similar [to software engineering]. I think where it differs is that I’m mostly thinking about a single person’s experience, or trying to translate my feelings into different people who would be using this rather than a generic persona.

It’s this feedback loop of sending it to friends or people in the community, that’s the difference in community-maintained software. You need to have a vested interest in it to make decisions, which should automatically align with the community. Then you can have this back and forth of changing it.

What signals to you that your pieces are nurturing community?

It’s very imprecise of a metric, but I feel like one of the things I turn to is emails from people. It’s interesting because it’s so ephemeral, untraceable, unfriendly to metrics, but still in the digital context of distribution. It does feel like my words and works are reaching people in different places and audiences I didn’t expect to reach.

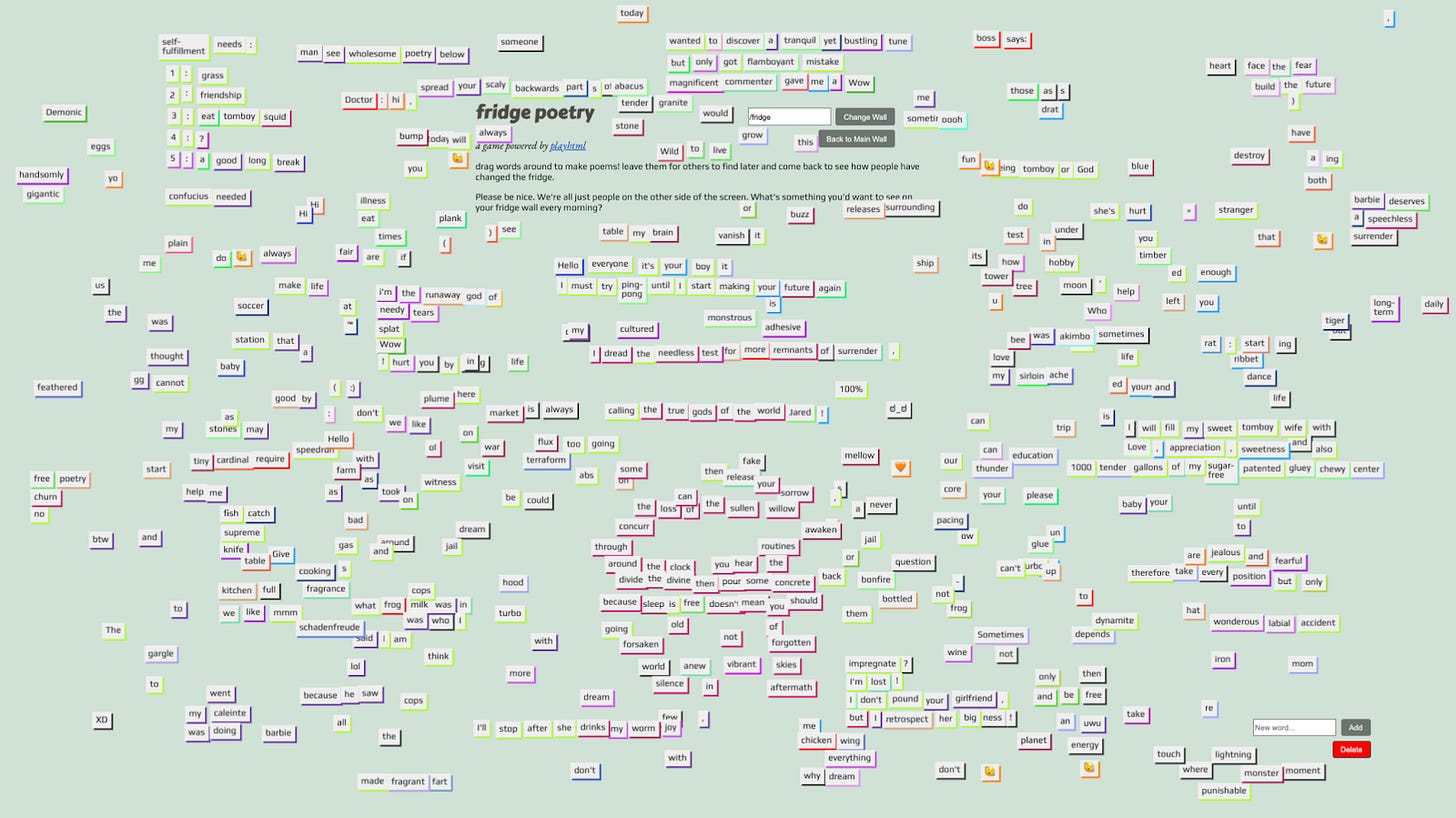

Once I made this fridge game (playhtml.fun/fridge) where everyone could add words and move them around. And it got picked up by a gaming magazine (Rock Paper Shotgun), and it reached people that were very much not the typical internet native audience.

Whenever it [my work] breaks out that containment, that does give me hope about the broader applicability of it and it’s where I want my work to reach in the future.

When you’re designing each of your pieces, are you actively thinking about a different audience?

Honestly, most of it starts from a specific part of me.

It’s really hard for me to design with full care when it’s not personal to me. So either it’s something that I really want or have, or it’s someone, you know, close to me that I’ve seen that struggle.

For example, my partner is someone who’s not online very much. And that’s actually a very grounding, helpful thing, because obviously I can design for myself, as an internet native. But I can also try to reach people who don’t like the Internet as much. That’s the duality I hold in my mind whenever I’m designing.

Is there a piece that shows that duality, of the internet native and the…maybe I’ll cut this out of the transcript, but the luddite-ness?

I think people are reclaiming luddite as a term!

Wow, okay, maybe I won’t cut that out.

The piece I think about is called everyday (commissioned by Hyundai Artlab), which is this interactive phone art, where every hour of the day there’s a prompt that invites you to interact with your phone in a strange, intimate way. So maybe it’s dancing with your phone, or showing it something beautiful.

All these strange things that highlight how this device is always with you, catered to the different things you’re doing at different hours of the day.

This was a piece where I had the most profound reaction from both sides. Where even people who didn’t care about what internet art was – I got them doing weird things with their phones.

And obviously it resonated with people who are on their phones all the time, who feel that ‘internet nativeness.’ That felt really cool.

A lot of our controversy about technology is focused on the phone.

There’s so much stuff focused ongetting away from the phone, but I don’t think the phone is inherently bad. It’s just that the phonehas been engineered to take our attention and create these negative cycles.

I feel there’s very fertile ground for subverting that perspective. It doesn’t have to be that way! It’s just been so ingrained into what we take for granted and how we use that technology.

There’s two dialogues that I personally see happening: there’s a dialogue with, let’s say another person, but maybe there’s also a relationship with the device.

The most core thing in all my works is that I try to get people who experience it to develop a sort of playful relationship to technology, because I think that’s what unlocks like the agency to change it. I think we feel the most control when we’re in this playful, whimsical mindset.

We reach our limits with technology when we feel we’re out of control, and that feeds a lot of these negative cycles with technology.

My hope is that people might look at technology in a different way. I’m just setting the scene for people to come and change technology.

One of your works is a pillow for the phone. It almost feels like you’ve embodied the phone as an extension mind and of the self, almost a personification of the device.

I think much of this lack of control you mentioned earlier is from the AI boom. People feel and fear AGI, ASI. How are you thinking about that?

I don’t think technology has ever been so deeply ingrained into everyday conversation. You can’t even step out these days without somebody’s dad commenting about AI! So I think that’s a good thing, where we’re being primed to think about how we want our relationship to technology to be.

Because for a long time, the technology industry dictated this progress.

My philosophy, which has stayed since I started working in tech, is giving people who don’t have any technical background the ability to shape and control software. And I think that’s been the most exciting part of all the developments to me.

You have people like my dad, who’s never touch code in his life, asking ChatGPT to make an app for him, which is pretty crazy.

I think that feeling of control will translate into the social media and other tools that we use every day. Why do I have to see the algorithm this way? Why can’t I control it? This is a question that Instagram has actually already been pushed to think about.

Obviously there’s the other side of this, like you see people having conversations only with chatbots, which is very dystopian. But I have hope that we can amplify the good kinds of agency and control for behaviours we don’t necessarily want.1

One of your current focuses right now is the social media aspect. We briefly talked about this earlier, but social media feels like it’s trying to sensationalize a lot of things. It’s so detached from the human experience, and your art is kind of doing the opposite, trying to bring it back to the interpersonal.

How do you think about using social media to promote or communicate your pieces when there’s that push-pull dynamic?

It’s really challenging ‘cause the current state of the internet is to have stuff reach a lot of people.2

I feel conflicted about having to translate my works or philosophy into formats that are prioritized by social media platforms.

For example, I’ve been making short form video because that’s what you have to do now. On one hand it’s an interesting challenge for my storytelling abilities. I do think it’s important to reach people where they are. That’s very core to my work.

I do think there’s a place for this type of embodied social media. I just wish the relationship with the platform would not be so adversive. It feels conflicting and sometimes paradoxical.

Earlier we spoke about technological stewardship and responsibility. What do you think graceful decay looks like [for your pieces]?

That’s really tough. I don’t feel like I’ve come to a great answer on this. I haven’t had to lay something to rest; I think there’s sort of these nice natural deaths.

It’s okay that GIF Cities is gone now, for example. I don’t think it’s a graceful decay to want to bring these things back to life, in their exact form.

I don’t know how you can tell, but you can feel if the life has moved on from these projects, or if the subject is not fit for what the primary concerns of your present life are.

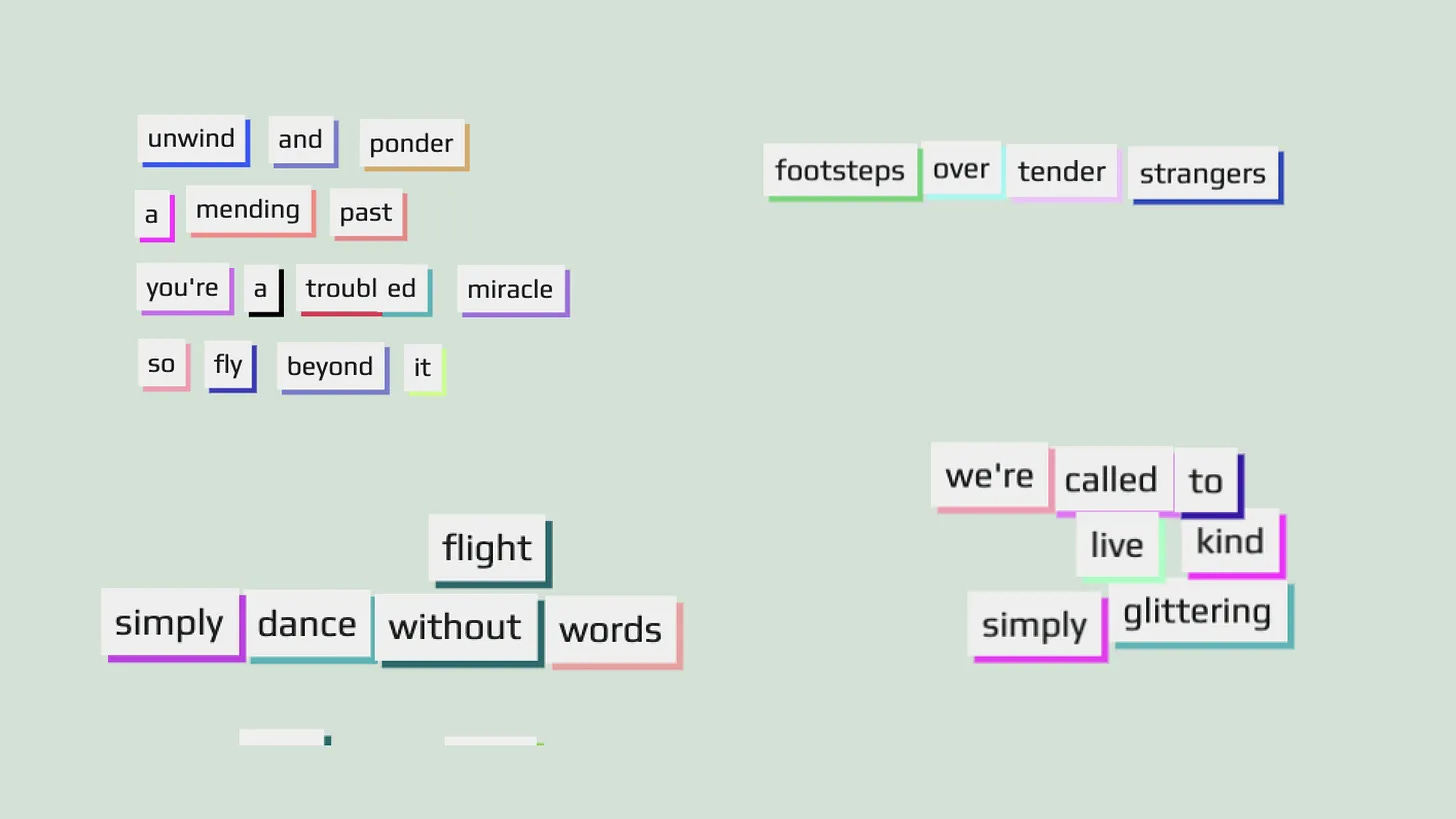

One small project I did last year – in a very new kind of format – was a piece that only happened on Instagram, for 5 days (Sharing Stories).

It used different Stories elements [in the app] to create interesting subversions or poems. You could make poems with the location tags, and people put all these different interesting messages saying: I love you, good morning, bagels are great [laughs] – anything you wanted. And whenever you added a photo to the story, it made a gradient out of the surrounding colors. All of the colors were from somebody’s actual photo on their camera roll, and this was another way of interacting with other peoples’ stories.

And then after the week, it was removed as if it never happened.

Not everything has to last forever. Some people will have this memory of it and that will affect how they think about things in the future.

Speaking of eras, I noticed that your outfits have changed a lot from when you were working in tech to now. How do you think your personal style and taste has changed? Walk me through the different eras of Spencer.

Wow! [laughs] Even when I was working in tech, it was a project to force me to exercise my creative abilities with my fashion.

I had a phase in college (there’s no photos of that) where I was just wearing tech t-shirts, brightly colored t-shirts with brightly colored shorts. It was not a good time.

You studied computer science?

Yeah, I studied computer science.

Ah, yes, that checks out.

[laughs] Yeah, that was a dark time. And then after I graduated, I did more of the “trendy” stuff, I started to experiment more after I started that log, because there’s only so many ways you can wear an outfit and after you’ve taken a picture of yourself, it feels bad if you’re wearing the same outfit.

So there are some really bad combinations in there, but oh well.

That formed some fundamental parts of my fashion philosophy – even until now – which is mixing things that you wouldn’t think go together or having a contrast, either in silhouette or color or texture or style. I like to mix masculine pieces with feminine pieces, this idea of the unexpected.

What’s the headline for your current style?

Duality.

Let’s focus on your most recent project – Computing Shrines. You’ve mentioned this feels like the culmination of your work. There are three lenses that you attribute to your work: playful, intimate, and empowering. Could you dissect this piece through those three lenses for me?

This piece is a series of sculptures that are designed to live in public spaces. Each piece has a different website embedded; it can only be accessed when a visitor brings their phone up to the sculpture. The websites themselves facilitate some sort of intimate digital experience with people who have visited that place.

The empowering part is that it’s designed to be sort of a template or protocol that other people can take and implement in their own neighborhoods. This was inspired by a lot of collective local practices, like little free libraries where you have a shared core format and people can take that and personalize it and adapt it to their own local customs and preferences.

What’s powerful about this piece is you have the physical sculpture, a location for expression, but you also have this digital space, this interaction aspect, to customize.

People are naturally able to think about what physical things they might want to change. It’s harder in a digital space, but I think when you combine it, some of that creativity or control or expression in the physical realm translates over.

The playful nature of it is that it’s fun to see people interact with it for the first time. It can be a little awkward sometimes! It also breaks this norm where you see a piece of art and you’re like, “oh, I can’t, I’m not supposed to touch it.”

This one actually requires you to touch it, interact with it, and also bring your device close to it. It naturally transitions into a very intimate experience, to put your phone into a strange new place and have some interaction with it – especially when you don’t know what’s going to happen.

For so many people, it’s even a primal fear, the act of giving up your phone. We were just talking about it - it feels like an extension of your body and an extension of your mind.

It can be very unnerving to give up your phone and offer it to these sculptures. For many of these pieces, you have to physically put it [your phone] inside the sculpture and release it from your hands in order for it to activate.

I do think of it as like an offering. There’s a ritual where you are relinquishing control of this digital appendage for a moment. And that is what allows you to have this liminal, connective experience with someone else.

One of them is about sharing your voice with a stranger. So you hear the last person’s voice and you get to share your voice [for the next person]. Just having it online would pose challenges, but in this physical setting, with this physical ritual around it, it led to a lot of very personal and heartwarming messages.

For the most part I’m still seeing how the empowerment part fully plays out. That’s the most challenging part of it. A lot of people have reached out to me to express interest in making their own version, but logistics is a lot of work.

But yeah – that’s why it felt like a culmination. It’s combined not only all these different parts of my craft, but also all these different aspects of my philosophy.

So this is an open protocol project. If I were a city planner and I wanted to adopt this, what are best practices you would relay over to them? Maybe with regard to stewards, rituals, data policy.

Well, I actually have been going through this process, with the city planning department, which has given me a lot of insight into this.

Many departments are not used to thinking about the digital side of art, and moderators are quite scared of it.3

Their focus when it comes to public artwork is focused on graffiti deterrence or preventing vandalism. But for this kind of work, I think digital vandalism is more of a pressing concern for them.

That’s not a very satisfactory answer. I still haven’t figured out exactly what the right answer is.

I have thought about personally moderating each one [interaction] and listening to them or reading through them every morning, and it could extend to the stewards of other places.4

There’s another line from you that says, “Towards flight and an internet that feels like ours.” How would someone feel or know that they’ve stepped into Our Internet?

Hmm. The most visceral, felt feeling would remind them of walking around in their neighborhood, or to a local café. There’s sort of this familiar, comfortable environment that also has a lot of diversity.

You can sort of travel between different internet spaces that all have their specific personalities. I think it also means you’re bumping into people. Sometimes it’s people you know, sometimes people you don’t know.

There’s a sense of community that’s embedded in it, whereas I feel like your general internet experience right now is very solitary. It’s like this disconnected experience.

In your neighborhood there’s a lot of agency for you to make changes, even small changes. At your local cafe, they might always give you your favourite cup! [smiles]

And there’s all this flexibility we don’t have in digital space. You would see and feel the changing of digital environments day over day. It would feel present. You would also see the effects of that from everyone around you.

Right now you sort of experience the internet and it’s always the same, or you feel like it’s changed completely. Like when Instagram moves the ‘Reels’ button into the middle of the screen – it’d feel like opening the door to your cafe’s restroom and it’s gone.

So rather than these drastic changes, I think there would be small, everyday changes that just come from someone being there. Maybe you’d see traces of someone who had read this article before you or, you know, people could leave inspiration, or little notes, or just these small embodied interactions… I think it would make it feel a lot more like ours.

Our last guest left you a question. It’s more meta, more abstract. He wants to ask: “what is The Question?” What is the question you’re asking with your work, and what is the answer that you’re trying to get to?

Hmm. What is the question I’m asking?

I think: what shape do we want technology to be?

And what’s the answer that you’re hoping for?

I think the answer is that technology is something soft, squishy, and moldable.

It’s something that you can throw at your friend. You can shake it. [laughs] They can take a piece off and throw it back!

I’ve never heard the word squishy as an adjective for technology before. Very creative. The last thing I’ll ask you is to pay it forward – a question for the next guest.

If you could make everyone experience something once, what would it be?

Beautiful. Everyone, this is Spencer Chang.

Thanks everyone.

Speaker’s Addendum. I resonate with these more fleshed out thoughts about AI from Frank Chimero, a designer and writer I admire a lot. I also like watching people subvert the function of AI by having fun with it or trying to break the system. This feels like the kind of tinkering that builds agency and teaches us that we are ultimately the ones in control of how we want machines to behave and what role we want them to play in our lives.

Speaker’s Addendum. I think a lot about “the breath of the gods” a term that Robin Sloan coined to designate your content being picked up by social media algorithms. These days, distribution is tied to pleasing the algorithm, and their idea of what will please people rather than directly engaging with people.)

Speaker’s Addendum. To the topic of data trust, I’m inspired by the pioneering experiments in this by Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst’s The Call, where the hosting gallery, Serpentine Gallery, serves as the data trust for the human data used for training in the project and facilitates compensation to those people. I’d love to explore similar boundary-pushing structures and governance models in future pieces.

Speaker’s Addendum. Reflecting on this, I think it’s hard to convey best practices because I think this field of interaction is so new, especially in public spaces and civic contexts. It’s very rare to have a technologically-interactive public artwork because typically, it is very infrastructure-heavy and requires staff to facilitate the experience. So having these interactive works that are allowed to just stay in public on their own is very new and experimental. I’d like to encourage them to be open to this, to lean into exploring this new field of art and listen to how the community responds to it.

Thank you, Spencer!

Computing shrines is such a lovely concept